Zhu Biao (1355-1392)

Born to become an Emperor

Zhu Biao and Empress Ma

On an early February day in 1355 baby cries echoed off the walls of young Zhu Yuanzhang's humble home. His wife had given birth to their firstborn child, a healthy boy, whom they named Zhu Biao.

Zhu Biao's mother, Ma Xiuying, was the adopted daughter of Kuo Tzu-hsing, the local commander and rebel leader for whom his father, Zhu Yuanzhang, was the most trusted guard leader.

Following the rule of primogeniture Zhu Biao was destined to grand things. As eldest surviving son he was the designated Heir Apparent to whatever estate his father would manage to create while alive.

Ma Xiuying

And what an estate! In 1368, just thirteen years later, his father enthroned himself as mighty Emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty.

Heir Apparent

In these rebellious years Zhu Biao didn't see much of his father while growing up. In 1355, Zhu Yuanzhang had just crossed the Yangtze River and established a new and independent power base south of the river centered around the city of Nanjing.

Although busy in his military endeavors, Zhu Yuanzhang still ensured that his offspring was raised with good Confucian values and was given great scholars as advisors and teachers.

After successful military campaigns which eventually ended the rule of the Mongolian Yuan dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang on 23 January 1368 in Nanjing proclaimed the establishment of the Chinese Great Ming ("Bright") dynasty and ascended the throne with reign title Hongwu.

As part of the proclamation, Zhu Yuanzhang's wife was elevated to the status of Empress, born Ma, and Zhu Biao was officially designated Heir Apparent.

Inscribed brick

Learned

Zhu Biao was now a Crown Prince at the age of just thirteen! He took up residence in the Eastern Palace (Dong Gong) of the Imperial grounds.

His father's most trusted generals were also appointed as his teachers to prepare him well for succession. Among those appointed were generals Xu Da and Zhang Yuchun.

Zhu Biao was quite different from his father in many aspects. He had a nice demeanor, a good temper and was a cultivated person. He clearly preferred a rule of civil obedience, moral values and indoctrination. These personal characteristics would later also be recognized in his son, the 2nd Ming Jianwen Emperor.

Although trained in basic military matters, Zhu Biao was neither a superb strategic general nor a physically brave person like for instance his brother, Zhu Di, who would later take advantage of these skills to become the 3rd Ming Yongle Emperor.

It all falls apart

As heir apparent he was sent on various official tasks for the empire. In September 1391 his father for instance sent him to Shaanxi province on an imperial peace keeping tour and to evaluate if the former Chinese capital of Xi'an would be a better and more secure capital for the empire.

He returned in December with maps and (unknown) recommendations but fell ill shortly afterwards and never really recovered.

Zhu Biao died prematurely on 17 May 1392, only thirty seven years old and six years before his father. His eldest surviving son (his first son died in infancy) was subsequently proclaimed as Grandson Heir Apparent and actually later ruled China four years as the 2nd Ming Jianwen Emperor.

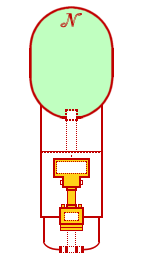

Dongling layout

Dongling used a triple courtyard design.

Uniquely for this tomb the front wall was curved. This cannot be found at any other imperial Ming mausoleum.

Apart from the stone foundations, the stamped earth platforms and the drainage canals, all above-ground structures are no longer extant.

Dongling is located just east of Xiaoling at Zhongshan mountain near Nanjing. A small, winding footpath leads from one tomb to the other.

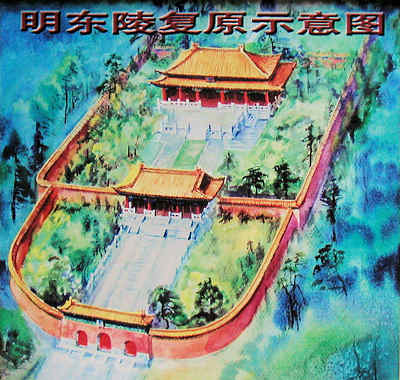

Artist rendering of Dongling (source: Local brochure)

Dongling

Zhu Biao's father, the Hongwu Emperor, had a mausoleum constructed for his son located in close proximity to his own mausoleum Xiaoling. Zhu Biao's tomb carries the name of Dongling, the "east tomb", simply because it lies only some 60 meters east of Xiaoling.

Dongling is to some extent a miniature model of Xiaoling. It has a surrounding wall, a front entrance, a sacrificial palace gate, a sacrificial palace and a treasure mound.

But that is where the similarities end because Dongling is equipped with some interesting and unique features which makes it stand out in Ming dynastic tomb construction.

Shared Sacred Way

The area in front of Dongling has been scanned and excavated several times but no trace of a "Sacred Way" is found anywhere. The evidence therefore strongly suggests that Dongling shared the Sacred Way of its neighbor, Xiaoling.

Dongling - forecourt and Sacrificial Palace

This construction approach set a precedence. The Sacred Way of the new and subsequent Ming dynastic imperial cemetery up north around Beijing led to the first tomb.

All later tombs in the Ming cemetery shared the same main Sacred Way. Individual tombs would be reached on smaller roads branching off from the main road.

And it didn't end there. The subsequent Qing Dynasty established two major imperial cemeteries around Beijing and also at both sites only constructed one single main Sacred Way serving all individual tombs.

Entrance with unique, rounded front wall

Rounded wall

The rounded wall

Dongling used a triple-court layout with a separate, front entrance gate. The gate was a simple construction with three doors and a roof covered with yellow-glazed tiles. Today, only the restored bases are extant.

Such gate can be found in other imperial Ming tombs, but none of them boast a rounded surrounding wall. This design is unique to Dongling.

The walls gradually curve inwards from the palace gate and are straight by the time they meet up with the walls extending from the palace gate further in -see photos above.

Palace gate east. Note the drainage canal

Stairs and plinths

Palace gate

The remnants of the Palace Gate, wall sections, plinths and platform, show that it was three bays wide and two bays deep. In metric terms it was 20 meters wide and 13.5 meters deep.

The front stairs had two levels, against the usual single level. There is a set of three stairs front and back and a single set again on each side of the main stairs.

Drainage canals extended from the eastern and western sides evidencing the high level of engineering skills of the late 14th century.

Palace Hall platform -west side

Passageway

Sacrificial Palace platform

Behind the palace gate is a small courtyard with an internal and elevated, stone paved passageway on the center line.

Trees have over time taken root at various locations. They were obviously left untouched during the restorations.

The platform of the Sacrificial Palace is relatively large. It measures 33 meters from east to west and 19 meters from south to north.

Brick

This is in fact so large that it could be suitable for an emperor although Zhu Biao was only a Crown Prince when he passed away.

Western staircase wooden replica

The extended front terrace has one flight of double stairs in the center along the internal "sacred way" but the traditional, decorated stone slab in the center is absent.

Another set of stairs also lead up to the front terrace on the east and west side. The original stone stairs have gone missing and have been replaced with a simple wooden, modern replica so as to still render an impression of how it used to look. This is a normal layout for a Ming and Qing Palace front platform.

The platform itself was built with multi layered stamped loess mixed with pebbles and was raised about one meter above the surrounding ground.

Plain bricks held together by a mixture of glutinous rice juice and lime mortar formed a retaining wall to ensure firmness and prevent collapse.

Plinths of the Sacrificial Palace

The terrace was originally lined with a stone balustrade but this has long since collapsed and the remains removed.

Sacrificial Hall

The sacred Sacrificial Hall was erected on top of and in the center of the platform. It measured 29 meters from east to west and 14 meters from south to north.

Water management

Apart from the stone plinths, which supported the circular beams of the construction, nothing of the original palace above ground has survived.

From the plinths we can ascertain that the hall was five bays wide and three bays deep, certainly a respectable size for a prince and even for many emperors.

Behind Sacrificial Hall -note the drainage

The Palace would have been covered by a single- or double-eave hip and gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles but no trace is left of it on the location.

The tomb mound

The underground palace contains the remains of Crown Prince Zhu Biao. It is not accessible, but one can walk on the tomb mound now overgrown with trees.

Terraced back wall to the tomb mound

The original soul tower has completely disappeared and no replica has been reconstructed in its place.

In Ming imperial mausoleums the Sacrificial area would be separated from the burial section by an east-west wall having a decorated triple gate in the center.

Zhu Biao's tomb has no dividing wall and is instead equipped with a terraced wall behind the Palace Hall area. Just east of the center there are remnants of a staircase.

Drainage system on eastern side

A small drainage canal in front of the terraced wall leads water away from the tomb area to prevent flooding.

Beveled columns

Flood drains

During a recent restoration the excavators uncovered the remains of an ingenious water discharge facility.

Smaller stone paved canals led water away from the buildings and platforms and into larger stone-walled canals alongside the outer walls of the mausoleum. The outer walls are long gone but the drainage system is almost intact.

The support columns supporting the cross sections of the canals were beveled so that they would offer the least possible resistance to fast flowing water from flash flooding. Moreover, the pointed column design reduced the chance for loose shrubs getting trapped by the columns and thus blocking the free water flow. Considering that the support columns are still extant bears witness to the smart design and wisdom of tomb builders over 600 years ago.