Zhu Yuyuan (1476 - 1519)

King Zhu Yuyuan

Doctors' verdict

It was late in the evening this day of July in year 1519. The king's doctors had just left the palace after passing their somber verdict of imminent death. Only a few candles now lit the bedroom of the king of Xing, Zhu Yuyuan.

He thought back on his life as a prince and later king. He was keenly aware that his family name of Zhu commanded respect because the Zhu family reigned China’s powerful Ming dynasty.

The king, Zhu Yuyuan (1476 – 1519), was born in Beijing Forbidden City as the fourth son of the 8th Ming emperor, the Chenghua Emperor (r. 1465 - 87) and the eldest son of three born to the emperor's consort, Lady Shao. She did not have rank of imperial concubine so dynastic provisions would never allow her son or his offspring to ascend the throne.

Being a son of an emperor however, Zhu Yuyuan was at least granted a fiefdom and made prince of - and, in adulthood, King of Xingxian (today's Zhongxiang, Hubei Province).

But on his deathbed Zhu Yuyuan harbored no regrets despite never having had a chance to rule China.

He had done his utmost to ensure that his only son, Zhu Houcong, would be well prepared to assume the reign of the Xingxian fiefdom. Born 16 September 1507, now a boy of 12 years, the princeling was a remarkably smart kid, able to recite Tang poems after only a few rehearsals.

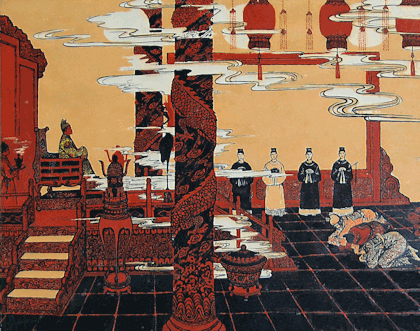

From an early age, Zhu Yuyuan had brought his son with him to royal ceremonies and rituals and had even allowed him to attend meetings with the senior advisors of the kingdom.

But Zhu Yuyuan had gone further than that. He had brought his boy with him on the annual trips to The Forbidden City in Beijing to pay his respects to the reigning Zhu family member, the Zhengde Emperor (r. 1506 –21). Not only did this teach the boy the inner workings of state level ceremonies, it also ensured that Zhu Houcong obtained exposure to the people at the very top of the Ming dynasty.

Even the Grand Secretaries of China, the people nearest to the reigning emperor, were familiar with Zhu Houcong and impressed with his skills and tactfulness. Zhu Yuyuan knew that such favorable impressions at the high Ming court would help his son when he succeeded his father as Prince of Xing.

Reflecting with satisfaction on his life and accomplishments, Zhu Yuyuan quietly passed away July 1519.

Little did he know that his son would go on to become emperor of China, the highest position of the Middle Kingdom, if not the world, and that even a mere two years later in 1521.

Little did he know how much his efforts in preparing his son for reigning the kingdom would actually prove to become a huge assistance at the most difficult time in Zhu Houcong ‘s first years reigning the entire empire as the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521 – 66).

And little did he know that he would die as a king but ultimately be intered as an emperor, albeit posthumously.

How did that come about?

But how could Zhu Houcong become an emperor when his lineage according to the rites forbade such promotion?

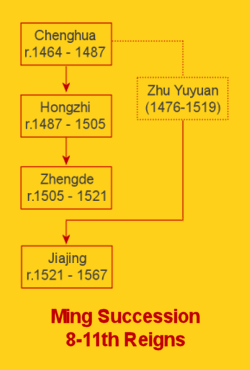

The Zhengde and 10th Ming Emperor died childless in 1521 so the proper approach was to choose the oldest surviving son of the previous and 9th Hongzhi emperor. But unfortunately none of the 9th emperor's sons was still alive in 1521. The imperial court then decided to go one step further back up the Zhu family lineage to the oldest surviving son of the 8th Chenghua Emperor. This would have been Zhu Yuyuan except that he had just passed away two years earlier in 1519.

The imperial court therefore decided to elevate the oldest son of Zhu Yuyuan, namely Zhu Houcong, to the 11th Ming emperor, reigning the Ming Jiajing imperial period (r. 1522 - 1566).

Zhu Yuyuan passed away not only unaware that his son would soon become the ruler of China but equally and happily unaware that he, a royal prince living quietly and loyally in his own fiefdom far away from Beijing, would become the source of a serious bone of contention at the Beijing high imperial court for several years.

From King to Posthumous Emperor

After ascending the throne Zhu Yuyuan's son, Zhu Houcong and now the Jiajing Emperor, insisted that his direct family be elevated to imperial status.

This was not a minor matter. For his deceased father such elevation would mean a mausoleum built to the standards of an emperor and hence -as it was believed in those days- a more comfortable afterlife in the netherworld. And for his mother this would mean a title of empress dowager with all the significant entitlements embedded in such a high position, including a better afterlife after she in turn would pass away.

Following a protracted "battle" between the emperor and the grand secretaries, it came to a final confrontation in August 1524 during which protesting officials were beaten, jailed and even killed on the Emperor's orders.

The emperor prevailed, and from that day on his family enjoyed full imperial status (see more details here).

And this is why the largest imperial Ming mausoleum came to be; namely the Imperial Ming Tomb in Zhongxiang, Hubei Province, containing the bodies of king Zhu Yuyuan (posthumously elevated to the title of Emperor Gong Ruixian) and his wife, Empress Dowager Zhangsheng.

The Xianling Mausoleum

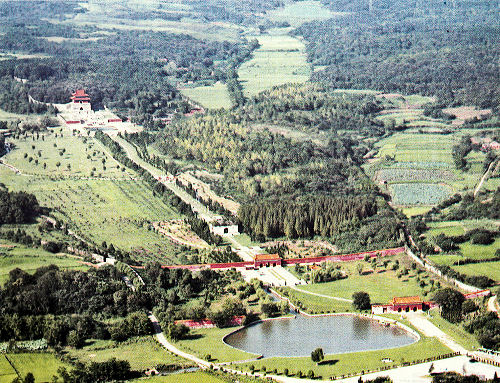

Construction of Xianling commenced in 1519 following the death of King Zhu Yuyuan. The site chosen for his mausoleum is located in the Songlin Hills, some 7-8 kilometers northwest of Zhongxiang city in central Hubei Province, the seat of his fiefdom.

The tomb was originally designed according to the standards of an imperial king, Zhu Yuyuan's royal status when he passed away. But already late 1521, his son, now the Ming Jiajing Emperor of China, ordered a complete rebuild of the mausoleum to become aligned with that of an emperor.

Apart from size and contents also the color scheme was completely replaced. For example, all black tiles used in buildings made for Ming kings were replaced by imperial yellow tiles, a color for instance prominently visible in all of the roof tiles of The Forbidden City in Beijing and a color reserved for the exclusive use in imperial structures.

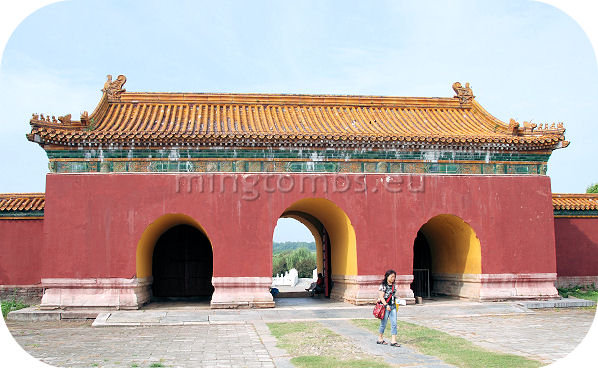

Outer Red Gate - the main entrance to Xianling

The Jiajing Emperor spent the next 37 years remodeling and expanding his parents' mausoleum, so that in the end it became -and still is- the single largest imperial Ming tomb in existence. Xianling covers an enwalled area of about 450 acres!

Construction was officially completed in 1566, some 45 years after commencement.

Xianling is even far larger than Xiaoling (in Nanjing), the tomb of the founding and first Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (r. 1368-1398), and than Changling, the tomb of the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402-1424), who was the first to be entombed in the huge Ming Shisanling mausoleum area north of Beijing, housing the tombs of 13 Ming emperors, concubines, princes and eunuchs.

Towards the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), peasant rebels being led by Li Zicheng (1606-1645) attacked the troops guarding Xianling, captured the mausoleum and burned down most of the wooden structures.

The subsequent Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) preserved the site leaving this historical monument for later times to enjoy.

Edict stele in front of

the tomb main entrance

How to get there?

Xianling is not easily accessible to today's traveler, which probably accounts for the relatively low number of visitors. Zhongxiang city lies some 4-5 hours' drive from the nearest large city with regular flights and trains.

It takes another 30-45 minutes by city bus or taxi to reach the mausoleum area from the center of Zhongxiang. Finally, you have to walk some 4-500 meters to the front of the mausoleum proper.

But if you wish to experience the largest -and also a well preserved- imperial Ming tomb, then it is worth the journey.

An Enwalled Mausoleum

In contrast to the famous Ming tombs at Mt. Tianshou north of Beijing, the outer wall that protects Xianling mausoleum is not set in straight lines and semicircles, but winds, curves and snakes its way around and up and down following the natural contours of the area.

Click here to see more photos from the front section of emperor Zhu Yuyuan's mausoleum

Click here to see more photos from the front section of emperor Zhu Yuyuan's mausoleumThe wall is almost 3.6 kilometers in length and has been well maintained. The height varies between 4-6 m depending on the natural contours and it is mostly 1.8 m thick, topped with yellow glazed tiles. Uniquely, it has a shape of a gold bottle.

The wall would be 1.6 km if in a straight line from north to south. The width is about 300 m in the north and the south but almost 460 m in the middle.

Despite of its huge size, the wall does not visually dominate the mausoleum since it is often hidden in the densely forested surroundings and completely blends in with nature.

The concept of a wall surrounding the larger area around the mausoleum and the internal wall was copied in Shisanling north of Beijing at Yongling, the tomb of the Jiajing emperor himself (r. 1522-1566), and later at Dingling, the tomb of the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572 - 1620), who succeeded the Jiajing Emperor.

Layout

The mausoleum design is a masterpiece and embodies the best construction methods in terms of material, architectural art, aesthetics and ancient tradition. Instead of intruding on the landscape, the man-made structures blend beautifully with their natural surroundings, leaving the visitor with the impression that it was all formed by nature with only minute additions.

Xianling is also incredibly rich on contents, virtually including any and all structures, which can potentially be erected in a traditional Ming imperial mausoleum. -And then some!

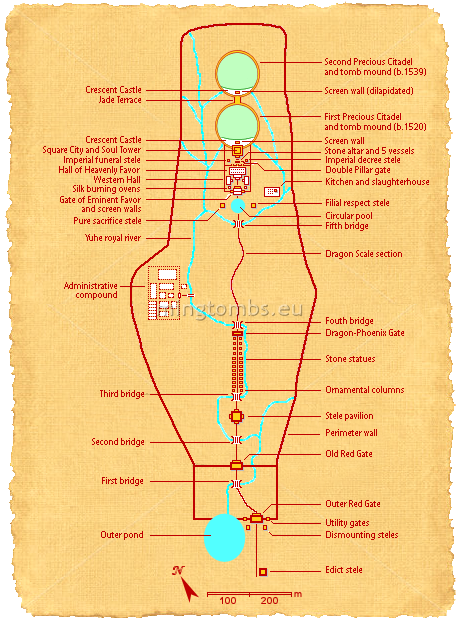

From south to north, one will find: Outer pond, mountain tablet, edict stele, dismount steles, new Red Gate, Nine-Bend imperial river, old Red Gate, imperial tablet pavilion, ornamental columns, stone animals and statues lining the Sacred Way, Dragon-Phoenix gate, inner pond, sacred kitchen complex, decorative walls, Gate of Heavenly Favors, side halls, Gate of Precious Citadel, Double Pillar Gate, Sacrificial Vessels, memorial tablets, Square City, Ming Tower, and (two) tomb mounds.

Red Gate reflected

in the outer pond

Add to the above, a large expanse of ruins of the administrative quarters west of the Sacred Way, yet still within the perimeter wall.

it takes maximum advantage of water and nature to divide the area into four distinct sections, separated by bridges crossing a single meandering water flow, the Yuhe River.

The river, which better could be described as a stream, has been nick-named "Nine-Bend Imperial River".

Outer Pond

Excavated in year 1539, an elliptically shaped natural pond adorns the western side of the main mausoleum entrance. The pond measures 120 m x 98 m and forms part of the outer perimeter of the tomb.

The pond is also an integrated part of the ingenious internal water flow, the imperial Yuhe River, through the entire length of the mausoleum, in Feng Shui philosophy allowing plenty of life giving "Qi".

More objectively, the water flow ensures drainage of the entire mausoleum, not just from rain water but also from ground level. The winding river serves as perfect catchment of rain running down the natural contours of the mausoleum area and beyond.

The pond is used for regulating the water level in Yuhe River inside the mausoleum and doubles up as a water reservoir for fire fighting.

Edict Stele and Dismounting steles

Dismounting stele east of the outer Red Gate

A lone stone tablet (see photo above) carried on a turtle back greets the visitor on his way up to the front gate. The tablet was originally housed in a spacious, square building measuring 7.5 meters each side, which however has long since perished. According to old records, the building had an arched opening on all four sides.

The tablet inscription contains general information about the construction and size of the mausoleum.

Right and left and a few meters in front of the first entry gate is a pair of dismounting steles, each 3.2 m tall, 0.8 m wide and 0.3 m deep. The top section has a cloud pattern.

The inscription states that all officials must dismount here. Also visiting family members -and even a visiting emperor- had to dismount their horses or palanquins.

Outer Red Gate and the Dragon Sacred Path

Xianling has not one, but two main gates. The first "outer" gate is an imposing triple door structure, 18.5 m long and 8 m deep. The single eave hip and gable roof is covered with yellow glazed tiles.

Crouching Dragon shaped Sacred Path

Middle "spine" flanked on both sides by "scales"

This gate was added to the mausoleum when it was promoted from a prince mausoleum to that of an emperor.

The base of the structure is made of white marble as are the stairs leading into and out of the gate. Lotus flower petals adorn the marble.

The perimeter wall adjoins both sides of the gate, on the western side however soon replaced by the bank of the outer pond. On the eastern side a square utility gate has been cut out of the original wall. Such later addition is not uncommon in Chinese imperial tombs and serves to allow today's workmen entering the tomb without damaging the main gate with their tools.

Traversing the Red Gate will bring one into a large, square fore court, where you walk a winding marble slated path and cross a bridge in order to arrive at the second main gate, guarding the mausoleum area proper.

The square has a significant and specific purpose. In the original layout from 1519, the square was in front of the (Old) Red Gate and hence outside the mausoleum proper. In compliance with geomancy principles, the square was large so that it could boost further development of the mausoleum as of the deceased.

Compare this to the inner square in front of Ling'enmen (see later) of the mausoleum, which should be smaller and had an entirely different purpose.

The winding path has a line of slab stones in the middle, which is perceived as the "dragon spine". Both sides of the middle is filled up with pebbles symbolizing the "dragon scales". Finally, a line of stones on both sides delineates the deity dragon lane.

The first bridge crossing the imperial Yuhe River

Xianling is the only Ming tomb, which follows this old Chinese tradition of a winding, dragon shaped sacred path. Not only this fore court has the dragon shaped Sacred Path; the later section of Xianling between the fourth and fifth bridge repeats this old tradition.

At the end of the dragon Sacred Path lies the first bridge crossing the internal, imperial Yuhe River.

The fully restored stone bridge has three parallel, arched spans. The middle one is both higher (2.8 m), longer (16.2 m) and wider (4.8 m) than the flanking ones, which are both lower, 13 m long and 3.5 m wide.

All the columns of the center span are top with a stone lion and its cub in various positions, but all facing inward. The center span balustrades all ends with a mythical beast with flaming hair.

The old Red Gate looking south

Inner or Old Red Gate

Having crossed the first bridge one arrives at the old Red Gate.

This gate was the main entrance to the original tomb when it was constructed in line with the rules governing a mausoleum for a prince.

Nowadays, the gate separates the entrance fore court from the ceremonial area and is flanked by a dividing wall stretching all the way to the perimeter wall. That wall was also the original front (southern) wall of the mausoleum.

In terms of design the gate is identical to the outer Red Gate (see above). Walls kept in imperial vermilion color, this 18.5m long and 8m deep structure is capped with a single eave, hip and gable roof covered with glazed tiles in imperial yellow.

A few meters west of the gate the diving wall bears signs of an earlier utility gate cut through the wall. This has however been restored except for the base.

Stele pavilion under restoration with the second bridge in front

Passing through this gate one enters the ceremonial section of Xianling. The stark contrast between the fore court and the ceremonial section is evident in the "Sacred Way", the marble path leading north-south through the mausoleum. Between the two entrance gates the path winds in gentle curves, but once inside the ceremonial section, the Sacred Way runs straight down the absolute center line of the mausoleum.

Second Bridge and the Stele Pavilion

A few meters past Ling'en Men gate one crosses the second main bridge inside the tomb.

As with the first bridge, this one also has three separate spans with the center one being slightly more elevated than those flanking it.

This bridge has not been restored and the balustrades are missing altogether.

Detail from the arched entrance

Further north lies the stele pavilion. At the time of the visit (June 2010), the pavilion was under complete restoration.

Each side of the square pavilion base measures almost 21 meters.

The pavilion has an arched entrance on each side. In most Ming tombs the rim of the arches are kept in an undecorated drab, gray color, but at Zhongxiang these rims are beautifully decorated with four dragons and pearl stone carvings plus, further down, with rock and sea patterns.

Stone statues with ornamental columns and third bridge in front

In the center of the pavilion is the traditional marble stele riding on the back of the stone tortoise. Many pieces of the original marble stele are unfortunately missing and have been replaced with matching new marble.

Third Bridge and the Stone Columns

North of the pavilion the fourth bridge gives entrance to the section of the Sacred Way, lined with pairs of stone figures. The bridge is similar to the second bridge and is also completely void of balustrades.

In front of each line of 12 paired stone figures is a stone column.

More photos from the stone figures to the ceremonial section here

More photos from the stone figures to the ceremonial section here

General and a tourist (right)

Each column stands 6.5m tall. The base and middle sections are hexagonal in shape whereas the top section is circular, topped with a coned shaped structure.

The middle section has a carved, subtle cloud pattern. Dragons whirling in clouds are carved into the top cone.

These columns have been part of the Chinese culture for centuries. Originally mainly used at palaces and tombs, they were later also used for showing directions and, made of wood, as a public notice board for people to post messages upon.

Meandering river

From south to north each row of twelve stone figures has a squatting lion, a squatting, mythical beast, a lying camel, a lying elephant, a squatting and a standing Kylin (one missing its head), a lying horse, a standing horse, two generals and two officials, the latter four all oversized.

The stone figures are all placed equidistantly to each other down each row.

On the eastern side behind the figures, the river meanders serenely between the third and fourth bridge.

Star Gate and Fourth Bridge

The stone figure section ends at the triple-gated Star Gate, just north of the figures of the officials. As is customary, the center of the crossbar of each gate is adorned with the famous "flaming pearl".

Dragon-Phoenix Gate with "Flaming Pearls"

(note person at center gate)

This gate is customary called the Dragon-Phoenix Gate, symbolizing that both the emperor and his empress(es) are entombed in the mausoleum.

Just behind the Star Gate, the Sacred Way crosses the fourth bridge over Yuhe Royal river. Also this triple bridge has no balustrades and the center span is slightly elevated compared to its neighbors.

Qu Shen road

The Dragon Scale section

-the winding Sacred Way imitates a dragon spine

The Sacred Way now enters an interesting and somewhat unique section of the mausoleum. The entire length is 290 meters from the fourth to the fifth bridge and has no particular decorations apart from being lined with evergreen trees.

The Sacred Way however is no longer straight but rather bends into a crouching dragon shape with two 30-40 degree curves. The curved path has two reasons:

First, Sand Mountain terrain next to this section prevents the path from going straight unless the harmony with the natural surroundings be disturbed. The quiet artistic effect creates a natural convergence perspective and renders a serene, soft winding pathway.

Fifth and final bridge over Yuhe River

Second, Feng Shui philosophy would impose curves. Evil spirits and arrows, and hence death, travel in straight lines so curves must be used to break or reduce bad luck and bad health.

The Feng Shui purpose may not be considered less scientific by many non-Asians in this century, but objectively the constructors succeeded in creating a natural harmony with the landscape.

As was the case in the southern section between the inner- and outer Red Gates, the marble slabs in the middle symbolizes the dragon "spine" and the cobblestone sections on both sides symbolize the dragon "scales".

The Fifth and Final Bridge.

The dragon shaped, curved section ends at the fifth bridge crossing the Royal Yuhe River for the last time inside the mausoleum.

Also the fifth bridge has three spans of which the middle one is elevated. But this bridge is still lined with balustrades, some original and some restored.

Each spans has eight columns each side. The columns carry a simple rectangular pattern and they are capped with a closed lotus flower.

Some 50 meters on both sides of the fifth bridge are two additional single bridge spans, presumably mostly used as service access. These bridges only have five columns each side, but these columns are adorned with small lion figures. These are however single lions and not the innovative ones with playful cubs, which for instance are found at the famous Marco Polo bridge southwest of Beijing.

The Circular Pond and Tablets

The square and circular pool in front of the Soul Tower

The square between the fifth bridge and the mausoleum proper entrance is occupied by a large, circular pool, flanked east and west by steles.

The square itself is an integral part the geomancy architecture, which dictates the layout of the entire Xianling. The square, being inside the mausoleum, is of modest size so that it can collect energy and conceal wind.

In contrast, the square outside the (original) mausoleum must be large so that it can boost further development. This larger square is today the section between the old and the new Red Gate.

The pool measures 33 meters in diameter and is rather shallow and flat-bottomed, similar in functionality to the "Reflective Pool" in Washington D.C. inasmuch as the tomb memorial stele tower is beautifully reflected in the pool surface. The pool edge is reinforced with a brick revetment.

Eastern tablet

This pool is unique feature since no other Ming tomb has a pool inside its mausoleum area. Consider that this mausoleum even has two pools, one cutting through the perimeter wall and the internal, circular one.

Apart from geomancy and decorative purposes, the pool also served as a more down-to-earth, large water reservoir for fire fighting as well as drainage control.

Some 50 meters east and west of the circular pool are square enclosures measuring 6.3 x 6.3 meters each containing a pedestal mounted stele tablet. The original pavilions covering these enclosures have long since been destroyed. The pavilion openings faced each other.

Western stele tablet

The western stele is 3.08 meters tall and the eastern one 3.18 meters, including base and top. The bases are adorned with floral patterns and the top of the steles carry the traditional two-dragons-and-a-pearl motif.

Erected in 1532, the eastern stele is 167 cm tall, 159 cm wide and 35 cm deep. The inscription is almost totally withered away from the surface and hard to read, but it was recorded in books at the time and hence the complete text preserved.

Mainly it describes difficulties surrounding the construction of the tomb and, specifically, it refers to difficulties arising from flooding due to heavy rains around Lunar New Year, and from rising water levels in rivers.

Also erected in 1532, the western stele stands 148 cm tall, is 103 cm wide and 24 cm deep; all in all, somewhat smaller than its eastern counterpart.

The inscription is still legible and describes the elevation of the adjoining mountain to a god-like status, being next to Xianling.

The Worship Section Entrance

Screen wall with dragon motif

Proceeding north past the circular pool the Sacred Way reaches the elevated platform in front of the burial section. The platform has staircase access on all sides.

On each side of the platform and in front of the wall are two large, dilapidated protective screen walls covered with yellow glazed tiles. The southern sides have green-glazed twisted branches whereas the northern sides have double laping dragon designs.

These Ming screen wall designs are unique to Xianling and cannot be found in any other Ming mausoleum.

Most of the glazed tiles on the screen face have fallen off and gone missing, but with some imagination one can still envision how foreboding these two large "shining" screens would appear to a visitor.

Ling'enmen or Gate of Eminent Favor

Door hinges and round column bases are still clearly visible

Three staircases lead from the large platform into the worship section. The wider, center staircase has the traditional, decorated marble stone down its center, the stone now having been covered with a protective glass. The decoration is quite eroded, but one can still recognize the dragons.

At the top of the staircases is the entrance gate -Ling'enmen, or rather, was the gate. Only the stone and marble parts remain, but from these we can see that the gate measured 3 rooms across and two rooms deep. The stone door mounts are also extant, evidencing that the gate had three doors.

The entire backside of the gate foundation has intact balustrades, which likely means that the gate had a single eave hip and gable roof without a front or back "wall". The open front would have relied on the glazed screen walls to guide the visitor to its doors.

Phoenix

The balustrades are mostly original and richly decorated. The top of the pillars each carry unique decorations as is often the case in Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing (1644 -1911) dynastic times. Since this mausoleum was made both for the emperor and the empress, some of the pillar top decorations depict a phoenix, the symbol of the empress.

Many more photos from the ceremonial section here

Many more photos from the ceremonial section hereAs in the front, three staircases lead down from the entrance gate platform to the large, square worship area. Also this wider center staircase has a marble slab down its center. This slab has three distinct sections: The top and bottom ones depicts the traditional dragon-phoenix-pearl-dance and the center one only has the emperor's dragon.

The Worship Section

The worship section looking south

The large rectangular ruins in the front is the Sacrificial Hall

Right and left in front of the hall are the side halls

and, in the rear, the gate flanked by screen walls.

Further back is the circular pool, the dragon scale road

and stele pavilion

This large area is square, because the Ming associated square shape with the earthly living beings, and this area was for the living to pay homage to the deceased buried further north. Similarly, oval and round shapes were generally associated with the deceased.

The section has three main structures: The sacrificial hall and two side halls. Remnants of two small silk burning ovens are also visible.

Foundation of western silk burning oven

Not much is left of the silk burning ovens. Only the foundations and some rubble remain. However, a few meters away the roof section of one of the ovens could still be identified.

These ovens were used to burn silk and symbolic money during the rites to provide for the deceased in the netherworld.

The eastern side hall was mainly used as a storage house for silks, sacrificial furniture, material, repair tools etc. The western hall was used for ritual chanting by monks and for changing of robes.

Each of these halls was 22.2 meters wide and 9 meters deep. They were just one bay deep and five (small bays) wide. The extant plinths indicate single eave, hip and gable roofs with a front overhang for shade. Only one plain center staircase led up to the platform of each of these halls.

Main structures in the ceremonial section

- note the special, heated room for the Empress -

The main sacrificial hall -Ling'endian, or "Hall of Heavenly Favor" was an impressive 31.1 meters wide and 17 meters deep. It was a massive structure, five large bays wide and two large ones deep. It was covered with a double eave, hip and gable roof.

Center staircase to front platform of the Sacrificial Hall

All woodwork is now gone, but from records it is known that the ceiling was covered in jade and blade gold, the lattice doors were imperial red () and copper wired. Only the finest Nanmu wood was used for the huge columns, which supported the roof and created the bays.

A special heated room inside the sacrificial hall was reserved for the empress to ensure her a pleasant visit.

Ling'endian had a large platform in front. Staircases led from the square court up to the platform on all three sides, but only the front, triple staircase had a marble slab in its center. All the staircases had balustrades.

Gargoyles on all sides and corners of the platform ensured an effective drainage of rain water.

Gargoyle

Triple Gate

Only center gate had direct

access to the funeral section

Just like for instance in The Forbidden City, the gargoyles are shaped like a dragon head with the water spout located in its mouth, making the dragon spewing water when it rained.

The wall behind the sacrificial hall separated the dead from the living. The wall had the traditional "Triple Gate": The center one for the emperor and the two side ones for dignitaries.

Whereas the two side gates were simple, the center one was far taller and decorated with yellow and green glazed tiles and floral patterns.

To further emphasize rank, the center gate was directly accessible from the sacrificial hall platform, but to access the side gates one had to first descend a small side staircase of the platform and then ascend another one up to the gate.

The Back Courtyard

The burial section behind the last dividing wall contains the traditional Lingxingmen, or Double Pillar Gate, the five sacrificial altar pieces, the "Square City" topped with the "Soul Tower", the "Crescent City" and not one, but two tomb mounds.

Burial Section

Left to right: Square City, altar, vessels, Double Pillar Gate

and Triple Gate

As an "extra", two tablets have been erected in front of and on each side of the "Square City".

Only a few steps north of the center "Triple Gate" is the "Double Pillar Gate". The woodwork is all gone but the two 6.75 meter tall side pillars supported by stone drums still stand.

On top of each pillar sits a mythical Kylin. In addition to protecting the burial section, the Kylins also portrayed peace and happiness.

Eastern stele with Imperial Edict

A few steps north of the "Double Pillar gate" is the traditional sacrificial stone altar with the equally traditional five stone vessels. The altar is carved from white marble stone and measures 1.1 meters high, 2.94 meters long and 1.48 m wide.

Somewhat non-traditional however, the standard five ritual vessels, - the incense burner, the candle holders and the vases - are placed on a separate low platform in front of the altar rather than on the altar itself.

Moreover, only the incense burner with its dragon motif is intact. One half of one candle holder is next to it and then there is some indistinct third vessel on the other side. Two pieces are missing altogether.

These vessels only served symbolic purposes and have no practical use.

Square City center access

Many more photos from the funeral section here

Many more photos from the funeral section hereRight and left of the sacrificial stone altar are two memorial steles each being 3.5 meters high, sitting on top of a turtle back, capped with a traditional dragons-and-pearl motif and housed in a small ruin building measuring 6.32 X 6.35 meters.

The eastern stele inscribes the imperial endorsement and decree ordering the construction of the mausoleum.

The western stele is engraved with the imperial funeral orations.

Steles, steles, steles

Xianling mausoleum is gifted with an unusual high number of steles, in fact, more than any other Ming mausoleum.

Not counting the two dismounting steles, a total of some 8 steles have been erected in and around Xianling by the Jiajing Emperor. All the steles except for one were placed inside a pavilion or a tower. Only the restored Soul Tower and the Stele pavilions remain.

But the Jiajing Emperor went far further in his quest for erecting steles. Back in Shisanling, the Ming mausoleum at Tianshou Mountain north of Beijing where most Ming emperors were interred, the emperor ordered the erection of a stele in a pavilion left of Changling front gate.

But he didn't stop there. He went on to having steles erected in front of the already existing mausoleums of Xianling, Maoling, Tailing, Kangling, Jingling and Yuling. None of the steles carry any inscription.

Moreover, subsequent Ming emperors followed suit and had a bare stele erected in front of their own tombs.

Square City, Crescent City and Soul Tower.

Crescent City

Left to right: Square City, Screen Wall and tomb mound

The Sacred Way ends at a wide staircase leading up to the "Square City", the large and tall crenellated platform on which the the Soul Tower rests. The stairs are dilapidated.

The layout of the Square City differs significantly from tomb to tomb. Some have stairs on both sides leading up to the Soul Tower, whereas others have similar stairs in various shapes in the back, as is the case in this mausoleum. Some of them - notably during the subsequent Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) - had access to the funeral chamber in its middle. Some were solid with side doors and some, as is also the case in this mausoleum, had an opening through its center from front to back.

Restored Screen Wall inside the Crescent City

The front and back arched entrances into the Square City is beautifully adorned with white marble stone and dragon motifs. Originally, the openings had a heavy, wooden door, but these have long since rotted away and not been replaced.

Walking through the Square City one enters the "Crescent City", so named simply because this courtyard has a crescent shape. More interesting is its other nicknames of "Mute's Yard" and "dumb yard"; these folklore names stem from the myth that only very dumb workers or illiterate mute workers were allowed to work here as they would become privy to the secret entrance and access way down to the funeral chamber.

A glazed tiled screen wall stands with its back to the tomb mound and on both sides of the back of the Square City is a staircase leading up to the top and the "Soul Tower".

Memorial stele

The majestic Soul Tower was originally constructed in 1527 but destroyed during the civil war following the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644.

Soul Tower

It was restored in 1990 back to its original imperial vermillion color and has a double eave, hip and gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles. The building has an arched entrance on all four sides, the edge decorated with white marble slates depicting ocean, mountains, dragons and clouds ( = "Heaven").

The inside is painted yellow. The memorial stele is erected in its center, resting on the back of a turtle. The stele is 4.55 meters tall and 1.29 meters wide, faces south and carries an inscription saying, "Gong Xian, Emperor Ling Duo". The top section is inscribed with "Da Ming" ("Great Ming") surrounded by the two-dragons-and-a-pearl motif.

The Precious Citadels and Tomb Mounds

On the rampart of the Precious Citadel

The "Precious Citadel" is name given to the crenellated protective wall encircling the earth mound under which lies the underground palace where the deceased's coffin is buried.

Uniquely for this mausoleum, there are two separate Precious Citadels and two tomb mounds, the citadels connected with a rectangular wall.

The oldest (southernmost) Precious Citadel is oval, measuring at its widest point about 112 meters east-west and some 125 meters north-south and with a total circumference of 396 meters.

It was constructed in 1520, the year after King Gongruixian (aka. Zhu Yuyuan) passed away. He was still "only" a king at the time of his death, since his son only became emperor in the year 1522.

He was laid to rest in this underground palace in 1520.

Steep access

The citadel wall is some 3 meters wide at the top. It is crenellated for armed defence on the outside. It is slightly slanted outwards so that evenly spaced gargoyles shaped as dragon heads in the outer wall allow for water drainage away from the tomb mound during heavy rains.

The inner wall has no crenellation and is only slightly more than one meter high.

The Jade Terrace, which connects

the two citadels

Interestingly, and somewhat unusual, a steep, but formal staircase leads from the back of the perimeter wall down to the foot of the earth mound. Visitors have already trodden a walk path from this rear staircase, up to the top of the tomb mound and back down to the Crescent City at the front.

When in 1538 the Jiajing Emperor's mother, the empress dowager, passed away from an illness, he was undecided as to whether he should bury her in the capital Beijing or together with her deceased husband in Xianling.

Many more photos from the Precious Citadels area here

Many more photos from the Precious Citadels area hereHe dispatched officials to Xianling to assess the feasibility of the latter option. When they opened up the underground palace they discovered that water had begun to flood the chambers.

The Jiajing Emperor therefore decided to construct the second and northernmost underground palace behind the original tomb. When this was completed he had both his father and mother buried in the rear underground palace or Precious Citadel.

His father's coffin was moved from the old underground palace to the new one through an underground tunnel located beneath what is today the "Jade Terrace" (see next).

Crescent City of the rear tomb

No Square City but a steep staircase

None of the two vaults have been exhumed and it is believed that grave robbers have never managed to enter the vaults.

The front and rear graves are connected with a rectangular, crenellated wall section some 14 meters wide, 40 meters long and 11 meters tall.

This connecting section is known as the "Jade Terrace", or "Jade Tower" meaning that this is a place where the Gods live. In other words, this connecting Jade Terrace leading from the first to the second citadel signifies that the emperor has arrived in Heaven.

The Jade Terrace has been neatly restored to its former glory with new crenellations and drainage gargoyles.

The second Precious Citadel is located some 40 meters behind (north of) the older Precious Citadel. It was constructed in 1539 after the Ming Jiajing Emperor (r. 1522 - 1566) in 1524 had issued the final imperial edict, which elevated his parents to emperor and empress dowager.

This rear citadel is circular with a diameter of 110 meters and a circumference of about 332 meters.

Screen wall of rear tomb

Inside the southern wall is the Crescent City of the second citadel. Less resources have been spent on its upkeep (probably because of the fewer visitors), so it is far more dilapidated.

Since there is no additional Square City or Soul Tower, a steep and wide "road" allows direct access from the citadel wall down to the Crescent City. The incline is however too high for individuals to safely use this approach.

Regular staircases exist right and left for safe passage from the wall to the Crescent City. The incline of these would also enable the regular horse patrols access from wall to mound.

The traditional screen wall covered in yellow glazed tiles is extant but in such a poor condition that a supporting scaffolding has been erected to prevent the screen wall from collapsing.

Drainage

Local hawkers enjoying lunch

while playing Mahjong

Already in the 1500's drainage control was quite advanced and these tombs bear witness to that. Apart from the obvious draining of surface rain water away from the tomb mounds and citadels, underground drainages were used extensively to retain and divert water from the mounds, lower surfaces and courtyards.

The 1956-58 excavation of Dingling, the tomb of Ming Emperor Wanli (r. 1573 - 1620), demonstrated how successful the drainage control system had become during Ming. Albeit that the underground palace was a little musty due to its encapsulation in a huge pile of earth far below the surface, there had been no water leakage or water seeping into the burial chambers, even after almost four centuries.

How then did the ancient master constructors of Ming mausoleums prevent water seepage and how did they ensure no water build-up inside the underground vaults?

They employed three different methods in combination:

One of the entrances to "Dragon Beard Ditch"

First, the exact location of the underground vaults were carefully chosen so as to allow underground water to be easily redirected to the drainage system.

Second, the underground chambers were insulated from their surroundings by a layer of lime, which prevented seepage and also reduced the effects of internal moisture build-up.

Finally, elaborate drainage systems and channels led water away from the surfaces and into retaining streams, many of which were underground.

Dragon Beard Ditch

Having discovered the partial flooding of the front (southern) Precious Citadel when it was reopened in 1538 (see above), the Jiajing Emperor ordered a complete overhaul of the drainage system of Xianling to prevent reoccurrence.

Inside the funnel of

the "Dragon Beard Ditch"

First step was to make a proper insulation of the underground palaces using lime as the primary material (see above).

Second, the rear underground palace was built far deeper into the ground than the front vault, which is almost level with the surface. This layout took maximum advantage of the surrounding topography.

The third step was to create so-called "Dragon Beard Ditches", drainage canals which snaked around the underground vaults on both sides so as to collect water seeping into the ground and preventing it from entering the underground chambers.

Xianling has several pairs of these underground sewers, some of which surface before the Crescent City and some after.

Drain in Crescent City

A very conspicuous opening into one of the sewers can be found in the front Crescent City under the wall on both sides of the Square Citadel. The opening measures about one meter on all sides and had originally two pointed stone uprights across the opening to capture debris and prevent blockages in the sewers.

Both the front and rear Crescent Cities have such sewer openings in the wall on both sides of the Square City.

The "Dragon Beard Ditch" nickname is derived from the way that the beard of dragons is traditionally depicted (see image left).

Many other small and easily overlooked parts of the drainage system can be found in numerous places at the mausoleum (see image above). Mostly these are small inconspicuous holes by the walls or slabs with holes or sometimes indents in the courtyard floors.

Bricks

In general, great care was taken during the construction to only apply the best of materials the empire could produce or import. The standard, oversized bricks commonly used in imperial Ming palaces and tombs are also used at this mausoleum.

Brick manufacturer's name

Quality control protocol required brick manufactures and kiln owners to stamp their names and/or location into the brick, so that any manufacturing defects could be traced back to the origin.

All bricks were carefully checked in the quality assurance process. A brick that did not render the perfect sound when tapped with a hammer would immediately be discarded.

Kitchen and slaughterhouse east of Ling'enmen

The observant visitor can find innumerous such marked bricks in the walls and buildings at the mausoleum.

One of the photo albums accessible from this web page tells part of the story of the extremely strict requirements imposed upon the manufactures in order to allow them to become and remain an imperial supplier.

The world hasn't changed much these last 500 years!

The Kitchen

The sacrificial kitchen section is located just east of the main entrance to the ceremonial section as also east of the circular pool.

Plinths of the original slaughterhouse

encapsuled into today's management office.

Apart from the restored front outer wall and a well then little remain of the original above ground structures.

Originally, there was a 3-bay, single eave building in the rear (east) flanked by a 3-bay building both north and south, also single-eave. The roofs were covered by yellow glazed tiles, having rank of imperial structures.

All these structures have long since been destroyed but one can still find many of the plinths, which prove the earlier existence and location.

A few research excavations have confirmed the historical records detailing the location of the imperial kitchen structures

The side buildings were used to store sugar, wine and other sacrificial material and food ingredients. The rear main structure was used as a slaughterhouse of cattle, sheep and chicken as well as a kitchen for the preparation of traditional sacrificial offers.

Well

The kitchen compound even included its own well. The well is still there although it has long dried out. The well was conveniently placed just north of- and next to the rear slaughterhouse building.

Many more photos from the Sacrificial Kitchen and Administrative compound area here

Many more photos from the Sacrificial Kitchen and Administrative compound area hereThe original roof of the structure covering the well was different from all the other inasmuch as it had a large opening at the top. The ritual prescribed that the sacrificial food should not be prepared with pure "yin water" from the well; the water first had to be made divine from three essential light sources: The sun, the moon and the stars. Hence the open roof.

Ruins of the administrative compound

The Stele Pavilion in the far distance.

The kitchen compound today houses the mausoleum management office.

Administrative Compound

Bureaucracy was as necessary for a civilized society back in the 1500s as it is today. Once this massive mausoleum had been built it needed a large amount of officials to administer the tomb and its large environment.

A purpose-built compound was constructed to the west of the Sacred Way but still inside the perimeter walls to house all the various departments, which had permanent staff on the ground to do their job. The compound was relatively large with many buildings and rooms to accommodate the many officials.

Bridge crossing Yuhe River

side brook into the compound

The only access from the compound and into the mausoleum proper was a small and narrow bridge crossing an auxiliary brook fed by the Yuhe River. Considering the number of people having their daily business in the tomb area, this bridge would have been quite crowded at peak hours.

Amongst the officials living there were eunuchs in charge of rituals and eunuchs who were key masters and gate keepers. Some staff were in charge of tomb maintenance and upkeep and other tended the many orchards and vegetable gardens inside the mausoleum.

The remains of the entrance guard house

On the right the road leading from the bridge

into the compound.

A select group of wardens had the arduous task of securing the large, off-limits zone outside the perimeter wall. No one from outside was allowed to enter this zone and, on punishment of death, poaching and illegal logging were strictly forbidden.

The constructors had gone to great length to ensure that the mausoleum blend perfectly with its surrounding nature and that it would remain that way. This and the no-entry zone attracted wild game and, as a consequence, attracted poachers looking for an easy kill with the abundance of wildlife.

The same applied to the forests where the abundance of excellent wood tempted many a local farmer or craftsman looking for good timber. And anyone in need of fresh fish would not have to wait long in the well maintained and well stocked fresh brooks.

Model of the compound

The bridge center bottom

The many efforts over the centuries to preserve the natural environment surrounding Xianling have greatly contributed to todays incredible serenity of the mausoleum. There are few if any modern structures in sight anywhere from Xianling. And even the official entrance and toll booth are placed far away so as not to intrude visually on the mausoleum.

The administrative compound now lies in total ruin and disarray and it is hard to clearly discern the former structures with the exception of the front bridge and the guarded entrance. Even some of the foundations have withered away over time and many of the original brick and stone have been removed and used for newer structures elsewhere.

And with that we shall leave the mausoleum for an emperor who was never an emperor.