Ming Tombs - Eunuchs

Illiterate

The first Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398), was keenly aware of the many troubles suffered by earlier Chinese dynasties caused by misdeeds of powerful palace eunuchs.

Ming Eunuch Tombs

Very few Ming dynasty eunuch tombs have survived to modern times.

Most of the tombs were located outside protected areas and were dug out and robbed shortly after interment.

The best preserved eunuch tomb is Tian Yi's in western Beijing. He served three Ming emperors in the late 16th and early 17th century and died at the age of 72. His tomb has been converted into a eunuch museum, which you can see here.

The only other known Ming eunuch tomb is that of Wang Cheng'en, the eunuch who committed suicide with his Emperor in 1644.

He was given the special honor of being buried in a simple tomb some 50 meters from Siling, the tomb of his master, the last Ming Emperor Chongzhen (1627-1644), located in Shisanling, north of Beijing.

This page carries several photos from his tomb. You can find the details of his grave site here.

As a result he kept only a small number of eunuchs and insisted on only employing illiterate ones. This would make it difficult for them to meddle in state affairs.

He allegedly went so far as to announce that any eunuch found interfering in government affairs would be decapitated, although there is no record of him ever carrying out such a threat.

Castrated males

Eunuchs often originated from the lower levels of society. With a surplus of male boys, families would sometimes decide to have some boys castrated and then presented to the court as a gift. If their sons did well, the family could hope for rewards in return.

The court in turn also benefited from receiving such gifts.

The eunuchs protected the palace women. On punishment of death no man other than the Emperor and eunuchs was permitted to enter the Emperor's private palace quarters.

But eunuchs also handled many trivial tasks like tending to the Emperor's daily needs which could otherwise only be handled by consorts and female servants. They served as handymen for the many small repair and maintenance tasks around the private sections of the royal palace.

Eunuchs were less prone to get involved in corruption and striving for individual wealth and power since they had no need to cater for a wife or offspring. Or at least, so was the theory. Reality would prove over and over again that man's greed and thirst for power went far further than a desire to merely cater for one's own family.

Wang Cheng'en's tomb

Shisanling

Assurance

The medical profession had made good strides already in Ming times. But when it came to palace eunuchs tending the precious harem, nobody took any chances.

Every four years each eunuch was formally inspected for any sign of "male recovery".

Origin

For the linguistically interested, the word 'eunuch' has its origin in the Greek language, "Eunoukhos".

This is a combination of "eune" (bed or place of sleeping) and "okhos" (keeping, to have or hold). Or, in more contemporary language, "guard of the bedchamber".

Non Confucian

The eunuchs in Ming were only accountable to the Emperor, which gave them exceptional powers beyond the regular legal system.

Stele carrying tortoise

Wang Chengen's tomb, Shisanling

They were tutors and confidantes to the young heir apparent and in this capacity to some extent able to both influence the prince's opinions and shape his political direction.

But it is also easy to understand why the Emperor, tired from being inundated with Confucian values and government bureaucracy by righteous, well-educated Confucian ministers, would often prefer less formal discussions with his eunuchs.

The civil- and military officials were well aware of the value of the eunuchs. The latter having direct access to the Emperor, many officials attempted to push their agenda through the eunuchs rather than through the formal channels.

Eunuchs in each Ming Reign

The eunuchs may have been restricted to handle trivial chores in the imperial palace during the first Ming reign (1368-98) under the Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang. And the fact that eunuchs had no training in military matters and were illiterate ensured that no state disasters caused by eunuchs were encountered in the Hongwu reign.

Horse engraving on front memorial stele

Wang Chengen tomb, Shisanling

But this was soon to change.

During the short-lived 2nd Ming reign (1399-1402), many of the palace eunuchs in Nanjing spied on the Jianwen Emperor, providing the Prince of Yan, residing in today's Beijing, with valuable information in his successful campaign against the Emperor's attempt to purge the Prince.

The Yongle Emperor (1402-1424) deployed eunuchs to a far larger degree than his predecessors. He trusted them with important government missions and, in 1420, established the much hated and feared "Eastern Depot" (ED), a eunuch agency operating like a secret police bureau. The ED spied on military- and civil officials and even on the royal family. The agency operated beyond the legal system and was known for indiscriminate imprisonment and torture, occasionally even leading to 'mysterious' deaths. ED rightfully eliminated many internal enemies of the state, but the lack of accountability also allowed for personal vendettas and convictions on fabricated evidence.

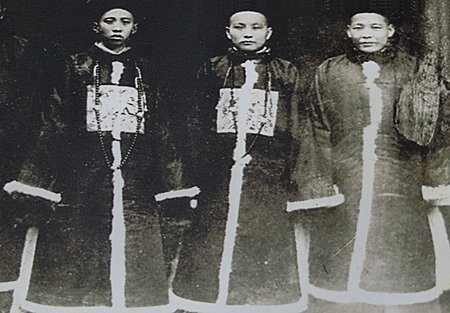

Palace Eunuchs, Tianyi eunuch museum

Things took a major turn in the fifth Ming reign (1425-1435), when the Xuande Emperor established a formal academy for eunuchs. This was a stark diversion from the tradition set by the first Ming emperor, who only would only allow illiterate palace eunuchs. Eunuchs would and could from now on handle official documents. Seriously augmenting the power of the eunuchs, the Xuande Emperor also empowered the prestigious eunuch department of 'Directorate of Ceremonial' (DOC) with the handling of proposals from the grand secretaries to which the emperor disagreed. DOC could decide on such proposals on behalf of the Emperor without first consulting him, which essentially placed huge power in DOC's hands, if left uncontrolled.

The sixth Ming reign (1436-1449) under the Zhengtong Emperor went further and saw the first usurpation of ultimate power by a eunuch. Eunuch Wang Chen had been appointed to the almighty DOC in 1435 and when the Zhengtong Emperor ascended the throne a year later, only eight years old, Wang became one of the six-member regency governing China under the control of Empress Dowager Chang. When she passed away in 1442, Wang took advantage of his closeness with the boy emperor -having been his first teacher and confidante- to dominate him and, eventually, push out the other regency member, making the Emperor's powers his own. Eunuch Wang Chen, and the empire, paid dearly for his power thirst and arrogance when he was killed in 1449 in the so-called T'umu incident, the disastrous outcome of an ill-conceived military campaign by a Ming army against the Mongols urged by Wang Chen and led by the young Emperor. The first Ming Emperor's fears of major eunuch disasters had come true less than a hundred years later.

Tomb mound of Wang Chengen's grave, Shisanling

Despite the serious public anger over the abuse of power by eunuch Wang Chen directly causing a catastrophic capture of the Emperor and loss of the imperial army, the eunuchs' power remained strong in the army and the court in the seventh Ming reign (1450-1456) under the Jingtai Emperor. However, the most powerful eunuch and head of DOC, Qing An, miscalculated in supporting a failed appointment of a new heir apparent, and lost influence when the sixth emperor was reinstated as emperor of the eighth Ming reign (1457-1464).

Masonry detail

Under the patronage of the wicked Lady Wan, favorite consort of the Chenghua Emperor (1465-1487), eunuchs exploited the empire on a massive scale during this the ninth Ming reign. Eunuchs began to issue edicts of appointments on their own, effectively selling off titles and positions, which allowed plunder of the prefectures. Many of the abuses seen in subsequent Ming reigns were modeled on those created in the ninth reign. As if the "Eastern Depot" (ED) secret police wasn't bad enough, the Chenghua Emperor authorized the establishment of a similar, but even worse "Western Depot" (WD), headed by yet another evil eunuch, Wang Chih.

Eunuch, Qing dynasty

The Hongzhi Emperor of the tenth Ming reign (1488-1505) rooted out most of the massive corruption of the ninth reign. The powers of the ED and WD was reduced to simple investigative tasks and loyal, honest officials were appointed as heads, replacing corrupt eunuchs. Direct appointments were abolished and thousands of irregularly appointed officials were summarily dismissed. Eunuch power was curtailed and the court was again able to attract able and honest officials. The Hongzhi reign is generally recognized as having the largest number of loyal eunuchs cooperating in tandem with good officials.

But it was to be a brief reprieve. Already in the eleventh Ming reign (1506-1521) the Zhengde Emperor allowed and even instilled excessive power in the eunuchs. Despite many complaints, eunuchs were in charge of most state matters, from imports, mining and manufacturing to tax collection and even military management. Several prominent eunuchs stood out as taking effective control of the empire. The Emperor left state matters to his eunuchs, who were quick to seize the opportunity for personal gain and power.

Even though the Jiajing Emperor (1522-1566) purged powerful eunuchs early in this twelfth Ming reign, his goal was mainly to make way for his 'own' eunuchs in powerful positions. Provincial eunuch power was curtailed but within the administration and court the eunuchs now rose above the grand secretaries. By combining the posts and placing a eunuch as head of both DOC and ED, the emperor had de facto removed checks and balances of the eunuch administration. In 1552, the Emperor even established a separate Palace Army comprised solely by eunuchs.

Wang Cheng'en's tomb seen from rear

From right front: Tomb mound, memorial tomb stele,

tortoise mounted tomb stele and name stele

The Longqing Emperor of the thirteenth Ming reign (1567-1572) engaged little in state affairs and by default allowed the fight for power between the eunuchs and the civil officials to prevail unchecked

The Wanli Emperor of the fourteenth Ming reign (1573-1620) resented the eunuchs, whom he perceived as having imposed constraints on him in his early reign period. A notable exception was his staunch support for the many eunuch tax collectors, whom he had personally organized and tasked with finding new tax revenues. He was particularly supportive of the new, highly controversial and unpopular mining- and commercial taxes. The number of eunuchs increased significantly in this period.

Dragons adorning the top of the memorial stele

Wang Chengen's tomb, Shisanling

It is alleged that the fifteenth Ming reign under the Taichang Emperor only lasted 26 days in 1620 partially because a palace eunuch sympathetic to a palace consort, whose son had rivaled the Emperor for the succession, had given the Emperor some bad medicine.

Eunuchs unsuccessfully attempted to interfere in the succession to the sixteenth Ming reign (1621-1627) but leading officials forced the rightful enthronement of the Tianqi Emperor. Being a weak ruler, factional infighting intensified and soon another eunuch, from the powerful position as head of ED, assumed political control of the empire and brutally purged his opponents.

The Chongzhen Emperor, head of the seventeenth and last Ming reign (1628-1644), commenced his rule by eliminating the ruling eunuch clique, reinserting civil- and military officials into the important positions, all with the goal of establishing a balance in the court factions. Already a few years later he was so disillusioned in the capabilities of these officials that he again used eunuchs for investigations and inspections. At least the eunuchs provided unfiltered information directly to the Emperor. In the end, only the eunuch palace guard was there to defend the Emperor, when the capital was overrun by rebels in 1644. And it was a faithful eunuch, who committed suicide next to the Chongzhen Emperor when the latter hanged himself.

Group of Eunuchs, Tianyi eunuch museum

Evil Eunuchs ?

These castrated males are often stereotyped as evil and catalysts in bringing about the fall of the Ming. But this is likely an unfair generalization, which could equally be applied to many other groups such as ministers and palace consorts.

First, eunuchs were not necessarily a coherent group acting in unison towards a single objective of imperial power. Eunuchs were by and large as divided on their allegiance as any other group of the Ming court.

Second, eunuchs were not confined to making intrigues in the palace court but carried out a huge number of tasks for the empire outside the palace walls.

Apart from the traditional roles of tending to the needs of the Emperor, the palace and the consorts, they also over time engaged in jobs as diverse as special investigators, tax collectors, soldiers, envoys to foreign rulers, supervisors of foreign trade, military commanders, admirals, palace guards, managers of state monopolies and businesses, managers of imperial granaries and storehouses, just to mention a few.

Third, although tales are plentiful of abusive eunuch power in the Ming dynasty, there seems to be a strong inverse correlation between eunuch power and capable rulers. Emperors, who were adept administrators and who engaged heavily and sincerely in state affairs, successfully limited eunuch influence in court and, in turn, took advantage of the confidence in and direct responsibility over the eunuchs to obtain information necessary to steer the empire in a right and just way.